From a packaging perspective, the more sustainable option is often assumed to be the option that looks the most natural, or organic — the one with less plastic, or less material overall. In many cases this is true, but the assessment of “sustainability” becomes more complex when the package’s contents are food — one of the biggest sources of greenhouse gas emissions when mismanaged and wasted.

In its recent U.S. Climate Summit, the Biden administration set the ambitious goal of reducing GHG emissions in the U.S. by 50 to 52 percent by 2030, compared to 2005 levels. It remains critical to keep the significant climate impact of the food system top of mind. The energy used to produce food and transport it to our plates is enormous. According to a United Nations study, one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions caused by human activity can be attributed to the way we produce, process and package food. And despite all the energy used to create this food, in the U.S. we throw away $43 million worth of it into landfills, where food waste emits greenhouse gases as it decomposes.

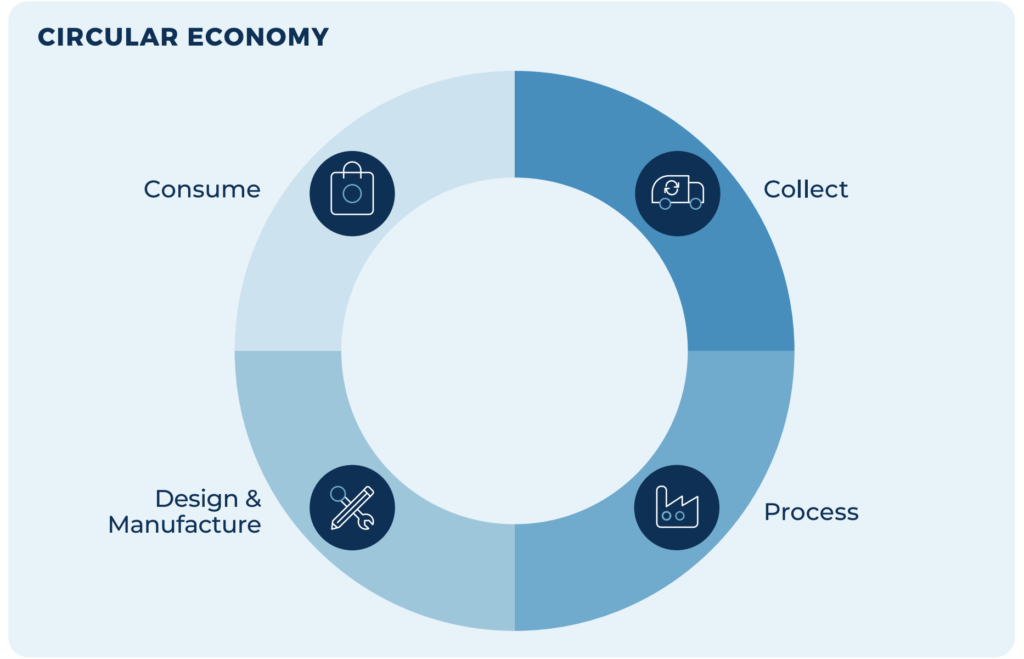

Since the earliest days of global food supply chains and industrial food manufacturing, food, food packaging and environmental impact have been intrinsically linked. At Closed Loop Partners, we invest in companies and business models that create innovative, waste-free solutions that prevent resource loss. When looking at the intersection of packaging and food, we believe that setting the course for a more sustainable path forward begins with three initial steps.

1. Consider the tradeoffs

Let’s revisit the cheese packaging options. The choices with bigger servings in their own rinds or in less packaging may seem more environmentally responsible overall, the rationale being the less packaging the better. And ideally the packaging used is widely recyclable or compostable. For households where all the cheese will be eaten within a certain time period, these options with little to no packaging might be the lowest waste option. But what if not all the cheese is eaten before it spoils? That’s food waste that could have been avoided if a smaller portion, albeit with a higher ratio of packaging to product, was chosen. Today, 31 percent of shoppers buy fresh produce in bulk to avoid unnecessary packaging. When aiming to reduce packaging waste, this is an effective tactic. But 53 percent of consumers have said that they waste more food when buying in bulk. According to the National Zero Waste Council, for many types of foods, “any GHG reductions achieved by not pre-packaging food are quickly outweighed by even a minor increase in food waste.”

57% of U.S. consumers want more resealable packages, and 50% want more variety in product sizes.

As eating and cooking habits change, more consumers today are looking for packaging that caters to storing food in their kitchens for longer, using small quantities at a time or buying smaller quantities at a time. Fifty-seven percent of U.S. consumers want more resealable packages, and 50 percent want more variety in product sizes. Particularly, they want to see baked goods, bagged salad, bread and meat available in smaller package sizes. How can we ensure that these preferences, which align with a reduction in food waste, can be met with more sustainable packaging options?

2. Invest in smarter packaging design

Innovation in packaging design can help reconcile the tradeoff between food waste and excess packaging. Smarter packaging works not only for the benefit of the food it contains, but also for the retailers and customers it serves. Emerging “active” and “intelligent” technologies help slow spoilage, giving information on food quality or safety, as well as enabling transparency across supply chains.

Where are we seeing progress? Closed Loop Partners invests in companies across the food and agriculture sector to strengthen every stage of the value chain — from farm to transport, retail, consumption, waste collection, food scrap and organics processing and back to the farm. We have invested in TradeLanes, a company that digitizes trade execution for container ships, increasing transparency in the global trade system to make the process faster, easier and more profitable. By better understanding where and when goods are in port versus in transit, we can ensure the right storage and create the optimal conditions for the transportation of food.

We’ve also invested in Mori, a company that has commercialized silk-based edible coatings that prevent food spoilage in transport and at retail and reduce the need for packaging. Its innovations — coatings applied directly to food, films to replace plastics — can be applied to whole or cut produce, prepared food, raw meat, seafood and processed foods. The edible coating is safe to eat, invisible, tasteless and virtually undetectable. Because it keeps food fresher for longer, less food goes to waste, which benefits the grower, farmer, shipper, processor, retailer, consumer and planet.

Improved package design and active and intelligent packaging also have a combined net annual financial benefit of $4.13 billion.

3. Collaborate to accelerate systemic change

To create system-wide change, stakeholders across the plastics and packaging and food and agriculture sectors and recovery systems need to be at the table together. We’ve seen the power of collaboration thanks to our work in the NextGen Consortium, launched by our Center for the Circular Economy to convene leading brands, industry experts and innovators to reimagine foodservice packaging and reduce waste. The Center’s new Compostable Packaging Consortium is deploying a similar pre-competitive, collaborative approach to identifying greater opportunities for the recovery of compostable packaging, in particular the role packaging can play in increasing food waste diversion from landfills.

In line with this work, we are partnering with the Sustainable Packaging Coalition (SPC) and its new initiative, Food Waste Repackaged. The initiative brings together experts and innovators to address the urgent challenge of food waste, exploring and advancing the role of packaging in addressing this waste in consumers’ homes, food service and retail and spurring new packaging innovations. Closed Loop Partners is proud to partner with SPC, together with GreenBiz, Packaging Europe, ReFED, RILA and Ubuntoo, on a Learning Series, Innovation Challenge and Mentorship Program to help tackle this problem.

When done thoughtfully and collaboratively, packaging reduction and design innovations present robust environmental, economic and social benefits. Preventing food waste is a top solution to climate change, and changes to packaging design could help prevent 650,000 tons of food waste a year in the U.S. Improved package design and active and intelligent packaging also have a combined net annual financial benefit of $4.13 billion. Catalyzing these solutions, and inviting dialogue across multiple stakeholders, brings us a step closer to building a more efficient, less wasteful food system.

.

.